During the past decade, in response to the global financial crisis, central banks in several advanced countries cut their interests rates to near zero. However, a few went even further – taking their rates into mildly negative territory. In 2019, an International Monetary Fund working paper said “the zero lower bound is not a law of nature; it is a policy choice”. In the aftermath of another financial crisis, this time caused by Covid-19, policymakers are once again weighing up the pros and cons of the policy.

The theory is simple – rather than hoarding money, depositors – forced to pay banks to hold their savings – are likely spend or invest instead. The policy’s main driver has been to stimulate investment in slowing economies, often along with large-scale injections in the form of quantitative easing. But do negative rates present an opportunity or a potential headache for finance directors in public sector bodies?

In some quarters, negative rates are frowned upon as an unorthodox tool. However, they are a perfectly legitimate economic response, according to Antonio Fatás, professor of economics at business school INSEAD, whose work focuses on the study of business cycles. “They are a standard fixture in the monetary policy toolkit, and appropriate when the economy is asking for them,” he says.

“It might well be that the biggest incentive to borrowing for investment may be in statutory requirements for economic development, rather than the Bank of England taking 10 basis points off the interest rate” Nick Keeling, Arlingclose

Public bodies may seek to take advantage of negative interest rates, at least in theory, for capital investment, says Nick Keeling, client director at UK local authority treasury advisory management firm Arlingclose. “If you are a public body that has been finding things tough in the Covid-19 environment, your borrowing is a priority,” he states. “So this tool is an attractive proposition.” However, he questions whether a move into negative territory would have a significant effect on public body borrowing. Sub-zero rates alone will not be the driving factor in spending decisions, he believes.

“Unless we go deeply negative, I don’t think you’ll see a negative bank rate spurring activity just by itself. It would need to feed through the yield curve,” he says. “All gilt yields would have to come down, so there would have to be some buy-in that it was a long-term policy. It might well be that the biggest incentive to borrowing for investment may be in statutory requirements for economic development, rather than a central bank taking 10 basis points off the interest rate.”

However, Keeling believes that being penalised to hold money in banks might have an unintended positive consequence on public sector operations – more effective cash management. Public bodies are likely to face a need to introduce more efficient cashflow management systems, or change policies for paying bills and wages, in order to reduce the cost of holding excess liquidity, he warns. “This will require better communication between finance department leads and the head of treasury, so that they can be certain about how much cash is coming in at any time,” Keeling says.

It may be new territory for some countries, but for parts of the developed world, negative interest rates have been a fact of life for many years. In Japan, the policy has been a core part of a policy aimed at kickstarting an economy that has stalled for the best part of three decades. However, in a country where large-scale public works programmes are the norm, negative interest rates have had limited effect in stimulating the economy, according to Robert Carnell, Singapore-based regional head of research, Asia-Pacific, at ING Bank. “Japan has proved that the impact of interest cuts below the 1% level are marginal, and may even possibly be having a negative effect,” he says.

Global experience

During the decade following the global financial crisis of 2007-08, more prosperous European countries, along with the European Central Bank, moved rates into negative territory (see infographic, p29). Professor Thiess Buettner, head of the Independent Advisory Board of Germany’s Stability Council, believes, even more than its European peers, Germany has seen great benefits from the decline in interest rates on government debt. He says the national government has taken advantage of the ECB rate cut to facilitate a big debt expansion to counter the effects of Covid-19. However, the impact on borrowing by sub-national government bodies has been minimal, he says. “Most of the action is at the federal level, providing support to municipalities that have not had to take on that responsibility and risk or worry about the ramifications of a negative interest rate policy,” he adds.

In Switzerland, the central government is set to increase public debt as a result of the pandemic, says Dr Angelo Ranaldo, professor of finance and systemic risk at the country’s University of St Gallen. The impact for authorities that have taken on funding in the negative interest rate environment is, at present, unclear, he states. “I don’t think there is any municipality or canton that is in trouble. So far, negative interest rates haven’t really had a significant impact, and there hasn’t been a big change in borrowing or in investment at the municipality level.”

However, existing debt portfolios might be affected, particularly where hedging strategies have been undertaken. In 2016, the Association of German Cities warned local authorities they may be exposed to “theoretically unlimited risk”, according to a report in business newspaper Handelsblatt. Relations between municipalities and their banks turned sour when expected payments from banks became liabilities.

Sweden

Local benefits

Sweden’s municipal authorities – the third tier of government below regional level – were the main beneficiaries of Sweden’s foray into negative interest rates. Launched in 2009, the policy saw deposit rates reach a nadir of -0.5% by 2015. The policy was abandoned in 2019, when rates were raised to 0%.

Fredrik Andersson, associate professor in the department of economics at the Lund School of Economics and Management, says the country’s central government had little need to borrow at negative interest rates during that period because the national debt declined in the years preceding the coronavirus pandemic. However, some municipalities running Sweden’s cities have “borrowed a little too much”, he fears.

“It means that if the interest rate goes up a little bit, they could experience problems,” says Andersson. “But, so far, financial problems have been experienced by only a relatively small number of municipalities in northern Sweden. None of the major cities have got into difficulty.”

Banking challenge

Such tests of the relationships between banks and public bodies are part and parcel of entering new territory – negative interest rates are as unfamiliar for the banking sector as for their depositors. In October, the Bank of England wrote to banks in an attempt to ascertain what issues their systems might face if rates were to turn negative in the UK. “Banks may find it difficult to deal with negative rates from the technology perspective, but it also might be a challenge in a conceptual sense, as we haven’t been here before,” Keeling warns.

“To help banks adjust, central banks have come up with tiered solutions,” says Fatás. In October 2019, the European Central Bank introduced a tiering system, which exempts a portion of deposits – currently set at six times a bank’s mandatory reserves – from paying more than 0%.

One argument employed against negative rates is that the policy exhausts central banks’ arsenals in a protracted war against the economic downturn, suggests Dr Nikolaos Antypas, lecturer in finance at Henley Business School. “Loose monetary policy can eventually become incrementally ineffective, requiring larger and more frequent liquidity injections to stimulate the economy, if recovery has not yet taken shape. This creates the obvious threat of making monetary policy an irrelevant remedy, while at the same time risking the advent of hyperinflation,” he says.

But what of the prospects for more widespread adoption of negative interest by central banks around the world? As the Bank of England considers the possibility of cutting rates below zero, a number of other countries that previously stated they would not countenance the policy – including New Zealand – are also signalling they could change their mind, says Carnell. At the very least, they are using the policy “as a veiled threat to keep their currencies weak”, he adds.

“As it becomes cheaper, local authorities and other public bodies will either borrow to spend money on services to enhance the public good or invest it. Both strategies could stimulate the economy.”

– Robin Jarvis, professor of accounting at Brunel University

Robin Jarvis, professor of accounting at Brunel University London, notes that while negative rates could provide a short-term solution to address the challenges posed by Covid-19, there is little appreciation of the impact over the long term. “As it becomes cheaper, local authorities and other public bodies will either borrow to spend money on services to enhance the public good or invest it,” he says. “Both strategies could stimulate the economy. But the loan still has to be serviced. Governments and central banks need to look at the experiences of other countries, as they have different structures in place,” he adds.

And if economic conditions improve as vaccine programmes are rolled out worldwide, enthusiasm for negative interest rates might tail off. Fatás believes the world is unlikely to see mass adoption, because quantitative easing has proved an effective means of stimulating economies. “As long as economic conditions keep improving, central banks might want to avoid negative rates,” he says. But, if 2021 is as extraordinary as 2020, local authority finance leaders must assume that the likelihood of employing this controversial tool is not off the table.

Germany

Federal response

Although Covid-19 resulted in a huge expansion of public debt, it has been the federal government that has taken on the heavy lifting, rather than the states, says professor Thiess Buettner, head of the Independent Advisory Board of Germany’s Stability Council. “Constitutionally, it’s the job of the states to provide assistance to municipalities,” he explains.

That has largely been made possible by a decline in recent years of annual interest payments on outstanding government bonds, asmaturity yields turned negative, says Buettner.

“Germany’s 10-year bond yields started to get negative around 2016, and now the yield is at -0.6%.” he explains. “This was a big windfall and provided an incentive to issue more debt.”

The low number of municipal authorities facing financial stress in recent years means they have not had to cut back on spending, says Buettner. But that may change, he warns, because long-term receipts from local business taxes are likely to fall away.

So far, a couple of long-term investment funds made available to authorities remain largely untapped, says Buettner. “Municipalities are a bit hesitant to use the funding for their own investment activities,” he adds.

But in states where municipalities have been allowed to use debt to fund current expenditure, he warns that problems may lie ahead.

Below the line

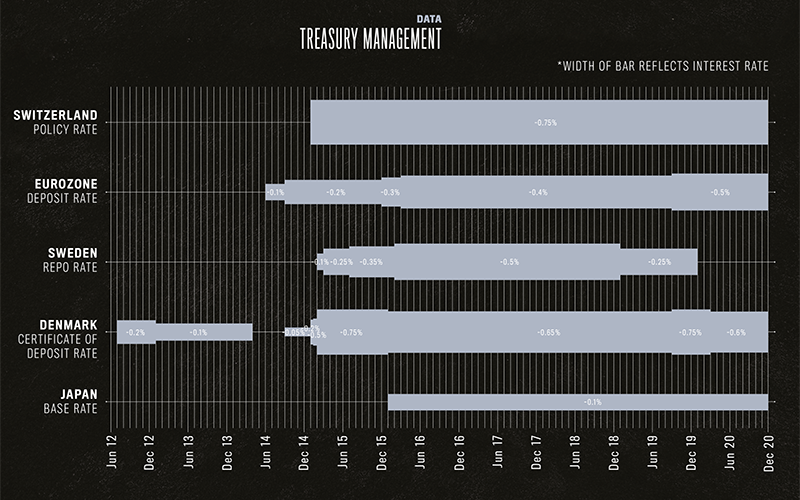

Negative interest rates have so far been adopted by five central banks in response to the 2007-08 global financial crisis. The first bank to take the plunge was Danmarks Nationalbank (Denmark)in 2012, followed by the Swiss National Bank in 2015. In January 2016, Japan reduced its base rate from 0.1% to -0.1%. Strictly speaking, Sweden’s Riksbank had become the first central bank to introduce a negative rate in 2009, when it imposed a negative deposit rate for commercial bank holdings. However, the main policy rate (the repo rate) remained positive until February 2015, when the Riksbank then lowered it to -0.1%.

The European Central Bank set the interest rate on its deposit facility negative in 2014, since when it has stayed below zero. It is now at -0.5%, and the rate is charged on any bank that holds deposits at the central bank overnight. This has only an indirect effect on interest rates charged by banks on their credit and on the interest on government bonds. Although the long-term rate set by the European Central Bank has never fallen below zero, the effects of the ECB’s quantitative easing programme of massive purchasing of government bonds in recent years (ramped up in 2020 to combat Covid-19) has seen the rate set by capital markets fall below zero. “The ECB’s main policy rate is zero. But because it supplies money through QE, the deposit rate (which is negative) also becomes relevant for the banks, which are flooded with all the additional money,” says Fredrik Andersson, associate professor in the department of economics at the Lund University School of Economics and Management.

This effect is felt in countries such as Germany when the maturity yields on government bonds turn negative. “Lower ECB rates (negative or positive) improve financial conditions for all borrowers, including governments,” says Antonio Fatás, professor of economics at business school INSEAD.