Zimbabwe rose in jubilation on 21 October 2017, when the speaker of parliament, Jacob Mudenda, read live on national television a letter by Robert Mugabe resigning as president.

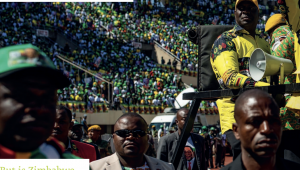

Mudenda was chairing a joint sitting of parliament, which was hearing a motion to impeach Mugabe. As this was happening, an aide of Mugabe walked up to Mudenda and handed him the 177-word letter. The chamber erupted in joy, as did millions who were following the proceedings on radio and television. This marked the end of a dramatic week for Zimbabwe, which saw the former strongman put under house arrest by the military, and a mass demonstration in Harare against his rule.

Mugabe, who died last month, had been in power for 37 years, running the southern African country with an iron fist and overseeing the collapse of what was once touted as one of Africa’s strongest and most diversified economies. Under his watch, the national currency collapsed, as did hundreds of businesses, condemning thousands into joblessness and poverty.

For a nation yearning for greater freedom and economic change, his resignation was a cause for celebration. Emmerson Mnangagwa, Mugabe’s righthand man for 50 years, took over on 24 November 2017 to complete Mugabe’s term. He got his own electoral mandate in July 2018 on promises to rebuild the economy, attract direct investment, re-engage western nations and uphold democracy and human rights.

Assessing Zimbabwe’s record after Mugabe, Gift Mugano, executive director of Harare-based consultancy Africa Economic Development Strategies, says the euphoria that marked the dictator’s fall has evaporated, as the economy and wellbeing of Zimbabweans have failed to improve.

“Inflation had risen to 176% year-on-year in June 2019, yet in September 2018 it was at 5%,” he tells Public Finance International.

“The current account deficit has declined, with imports worth around US$7bn in recent years [slipping] to US$5bn this year, versus US$4bn in exports. It is important to note, however, that imports have declined not because the country is now producing more but because of low demand amid falling disposable incomes. The other factor is the requirement that importers must pay duty in foreign currency, which is in short supply. In terms of exchange rate performance, we were at US$1 to Z$1 in November 2017, but now [at the time of writing] we are at US$1 to Z$10 on the official market and much more on the parallel market. Strictly speaking, the indicators show the economy remains in the doldrums.”

A drought during the October 2018-March 2019 growing season meant the country harvested only 776,600 tonnes of maize, far short of the 1.8m tonnes needed for annual national consumption of the staple. In early August, the UN announced that 3.6 million people would be food insecure by October. This will rise to 5.5 million by April 2020. It estimates that US$331.5m is needed to feed the hungry.

The country is also grappling with power load shedding for up to 15 hours daily. This is partly because of the drought, which has depleted the water level at Kariba Dam, where the country’s biggest hydroelectric generating plant is located, and partly down to the unavailability of foreign currency to finance imports.

Our future will depend on how we manage conflict. Politicians must put their houses in order, but, if they can’t, Zimbabweans must call them to order

Luxon Zembe, ex-president, Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce

Increasing inflation has left wages trailing far behind prices, worsening poverty. By the end of August, the cost of basics such as liquid fuels, bread, cooking oil and maize meal had tripled, and in some cases quadrupled, from January levels. This led to public protests in January, which were promptly crushed by the government. In mid-August, the main opposition party, MDC Alliance, called another round of protests, but police invoked a section of a contentious law to ban them, arresting 91 protestors.

In an effort to restore control of monetary policy, the government in June dropped the use of multiple foreign currencies, dominated by the US dollar, and reintroduced the local currency that Mugabe demonetised in 2009. As a result, prices have stabilised at high levels, but Tapiwa Gore, an unemployed economics graduate, believes the return of the local currency was ill-timed.

“A national currency can only be viable if we have foreign currency reserves, but we don’t,” he says.

“Also, a national currency can only be viable if it is backed by production, but we are barely producing, with imports always higher than exports. Also, one cannot expect industry to produce when they have electricity for only five to 10 hours a day because of load shedding.”

The West, which welcomed Mugabe’s departure, is now critical of his successor. In a statement on 1 August 2019, the US government said it had observed a deterioration in the state of affairs since the end of Mugabe’s rule.

“Zimbabwe is facing a worse political and economic crisis today than in 2017, when long-time ruler Mugabe was forced from power by the country’s military. Today, citizens are suffering under staggering inflation, regular fuel and water shortages, rolling blackouts, a failing currency, and an increasingly repressive political environment,” noted Senate Foreign Relations Committee chair Jim Risch in the statement.

Days later, EU ambassadors and their US counterpart issued a joint statement condemning a government crackdown that snuffed out the August 2019 opposition protests.

“Only by addressing concretely and rapidly these human rights violations will the government of Zimbabwe give credibility to its commitment to address longstanding governance challenges,” they said.

“The heads of mission reiterate their calls for the implementation of the government’s political and economic reform agenda, underpinned by inclusive national dialogue and increased efforts to address the severe social situation.”

The West’s tough views on Zimbabwe might complicate Mnangagwa’s drive to re-engage rich nations and unlock lending from international finance institutions.

As at June 2019, Zimbabwe owed multilateral lenders about US$8bn, of which US$5.9bn is accumulated arrears, according to government figures. The country is negotiating with the IMF to find ways to stabilise the economy and help it to clear the debt.

Although Mnangagwa’s administration has largely struggled to deliver, Mugano says it has scored a few successes.

Government has reduced spending and minimised borrowing. However, reduced spending has created problems, because the public system is collapsing

Gift Mugano, executive director, Africa Economic Development Strategies

“Government has reduced spending and minimised borrowing. However, reduced spending has created problems, because the public system is collapsing. People can’t get passports, because the registrar general’s office does not have money to import passport paper. Hospitals don’t have drugs. So, yes, it is plausible that the government is making budget surpluses, but in economics there is nothing wrong with running a productive budget deficit,” he argues.

Mnangagwa has done well to scrap an indigenisation law that prohibited foreign majority ownership of resources-based investments, says Luxon Zembe, a former president of the Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce. However, continuing wrangling between Mnangagwa’s government and the MDC Alliance is a source of concern.

“The record is mixed, but our future will depend on how we manage conflict,” Zembe says. “Politicians must put their houses in order, but, if they cannot, Zimbabweans must call them to order, because the economy of any country runs on sound politics.”

Three months after he assumed power, and consistent with his pledge to improve efficiency, transparency and accountability in the management of public finances, Mnangagwa launched a phased implementation of the accrual-based international public sector accounting standards to replace the cash-basis accounting system that government has been using since 1923.

The International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board is assisting in the effort, although progress is being hampered by resistance in some civil service circles.

Edwin Mushoriwa, an opposition legislator and member of parliament’s public accounts committee, says the government is putting in place systems until 2022, ahead of adoption of the new standards in 2024.

“The direction has been set and now we will see a lot of preparatory work,” he tells PF, adding that the new system will help [establish what] resources and assets the government owns. “We have lots of assets that are government-owned but cannot be accounted for using the current cash-based system.”

“If we were using IPSAS, this budget surplus that the minister of finance always celebrates may, in reality, be non-existent.”

Money transfer tax to reduce deficit

Introduced amid stiff resistance, a money transfer tax is helping boost government revenue, which, it says, is being spent on social protection programmes.

The tax, levied at a rate of 2% for every dollar transferred on mobile money platforms, was introduced in October 2018. It applies to transactions of at least Z$20. If a transaction is equivalent to or more than Z$750,000, the tax will not exceed Z$15,000 in a single transaction.

In an economy lacking physical cash and where mobile money transfers are the most widely used mode of transaction, the tax will potentially rake in substantial sums, said Gift Mugano, an economist and executive director of Harare-based consultancy Africa Economic Development Strategies. “It is painful, but it has helped reduce the budget deficit,” he said.

“However, we can do with greater transparency and accountability, so people see what their money is being used for.”

According to the 2019 first quarter report, released by the Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe in July, mobile phone transactions rose to Z$1.17bn from Z$1.05bn in the previous quarter. The report projected continued growth in both the value and volume of phone-based transactions.

The government has set a target of collecting Z$129m a month from the tax. About Z$449m had been collected by end of March 2019.

According to official data, Z$310m earmarked to fund the devolution of power policy this year would come from the tax. Salaries for 3,000 new teachers and 350 new university lecturers are also being paid from the revenues. In March, when eastern Zimbabwe was hit by tropical cyclone Idai, the treasury drew Z$100m from the tax to finance rescue and reconstruction activities.