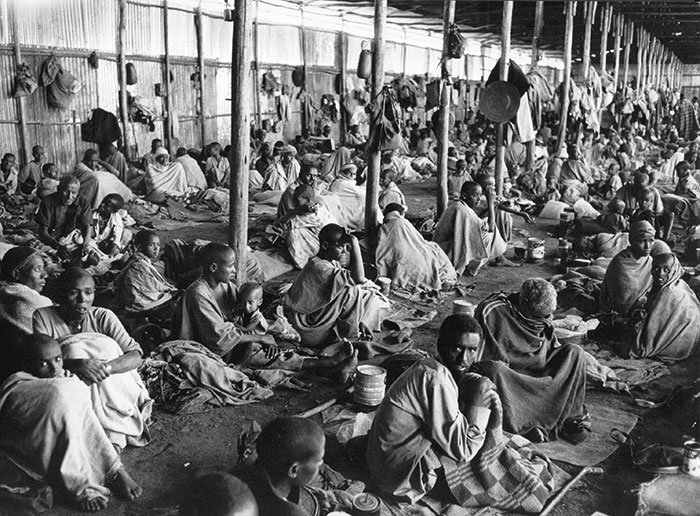

The horrific images of starving children desperately awaiting the delivery of food parcels and other aid may still be raw. However, 35 years since it was ravaged by a famine that killed an estimated 1.2 million people, Ethiopia has its sights on a future far more prosperous than its past. Live Aid catapulted suffering in the east African country into the collective conscience of the world in 1985, but in the three and a half decades since then it has become a very different place.

That time has certainly seen improvements to the lives of many Ethiopians: between 1995, when the country held its first general election following the overthrow of a military junta, and 2015, the poverty rate nearly halved, from 45% to 23%.

Between 2007-8 and 2017-18, Ethiopia’s economy also grew strongly, by an average of 9.9% a year, making it the fastest-growing economy in the region – and, in fact, the government aims to reach lower-middle-income status by 2025.

In recent years, the Ethiopian government has placed a heavy focus on long-term solutions to poverty, spending big on infrastructure and health. But it is on education that the country has pushed particularly hard.

That strategy is a good one, according to Grant Kasowanjete, global coordinator at the Global Campaign for Education. He says that investing in schools is a cornerstone of sustainable development, particularly in poorer countries.

“There are so many issues that education alone can solve,” he says. “If we want to achieve the sustainable development goals set by the United Nations in 2015, education is the centrepiece of that effort. Learned, knowledgeable citizens can demand their rights and push government to improve.”

He says education has a “huge role to play” in addressing societal inequalities, such as between rural and urban populations, social classes and genders. Referring to a well-known saying in development circles, attributed to renowned Ghanaian academic James Emmanuel Kwegyir-Aggrey, he says: “They say if you educate a woman, you educate a nation, and that’s really true.”

School enrolment has been very effective at the primary level, and particularly in terms of getting girls into schools, but it’s not just about getting people into schools; it’s about teaching them in a quality way, and that’s more difficult.”

Laura Hammond, SOAS University of London

The Ethiopian government seemingly agrees. Since coming to power in 1991, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front – the dominant coalition, comprising several regional parties – has set out education as a priority, investing hugely in schooling. As a result, Ethiopia is now the fifth-highest spender on education in the world as a proportion of its budget, setting aside 24.2%.

That investment has yielded results. Between 1996 and 2014, the number of primary schools nearly tripled from 11,000 to 32,048. In 2005, 10 million children were in school, but by 2015 that number had more than doubled to 25 million.

“Ethiopia has come a long way. It has had pretty impressive growth compared with many other countries in the region. The achievements since 1991 – when Ethiopia was emerging from 17 years of civil war – are quite impressive,” says Laura Hammond, an anthropologist at SOAS University of London.

There remains some way to go, however. While the increase in the number of people now in school sounds impressive, Ethiopia’s population under the age of 18 actually stands at about 47 million.

Furthermore, there are also concerns about a lack of focus on the standard of, and access to, schooling. According to an Ethiopian Ministry of Education assessment, between 2013 and 2016, around 90% of primary schools and 83% of secondary schools did not meet national standards.

School enrolment has had “really important impacts”, Hammond says, but there is clearly more to do.

“I think it’s been very effective at the primary level, and particularly in terms of getting girls into schools,” she adds. “But it’s not just about getting people into schools; it’s about teaching them in a quality way, and that’s more difficult.”

Poor education creates poor teachers, who in turn provide poor education. This cycle has had a dampening effect on the results of Ethiopia’s schooling.

But what impact is Ethiopia’s focus on education having on the wider progress of the country?

“In terms of quantity, the achievements are huge, not just in education but in health and other areas too,” says development economist Dr Zinabu Samaro Rekiso. “But, in terms of quality, there hasn’t been so much progress.”

Although the population is better educated, if the economy has not developed at the same rate, the productive potential of the newly educated population cannot be met.

Ethiopia is also hindered by ‘brain drain’. Between one-third and one-half of Ethiopian doctors work abroad, for example.

Rekiso, who lives in Addis Ababa, says the capital city is full of huge construction sites, providing some evidence of economic growth, but under the stewardship of the EPRDF, there has not been the necessary wholesale transformation of the way the economy works. “There has been some success in terms of social outcomes, but there are still serious challenges,” he says.

Nearly 84% of people are still employed in small-scale, rain-fed, low-technology agriculture. The jobs available to citizens have not kept up with their education.

Ethiopia also has an incredibly young population – around 70% of people are under 30 years old. Rekiso says youth unemployment is rife, because, conversely, the young are too educated as a result of the government’s emphasis on pushing as many people as possible through school and into higher education. Little attention is paid to what graduates will do once their studies are complete.

“The government should focus more on the quality of education, rather than on simply creating as many graduates and students as possible,” Rekiso says.

“Ethiopia currently produces 150,000 university graduates a year, but the government’s focus on job creation is on low-paying jobs, such as in the huge industrial parks they are building – mostly in manufacturing jobs in industries such as textiles.”

Even if much of Ethiopia’s economy has not changed in line with its overhaul of education, the EPRDF has. An ostensibly Marxist coalition during the civil war, because it came to power after the fall of the Soviet Union it has had to adapt somewhat to liberal capitalism – by that point the only game in town. But it has maintained its focus on alleviating poverty, and remains broadly to the left of opposition parties.

There are so many issues that education alone can solve. Learned, knowledgeable citizens can demand their rights and push government to improve.

Grant Kasowanjete, Global Campaign for Education

Late last year, prime minister Abiy Ahmed established the Prosperity Party – signalling a move away from regional and ethnic federalism – and for some time his statements have tended towards fiscal conservatism. ‘Austerity’, ‘living within our means’ and ‘tightening the belt’ are all concepts that have entered the national conversation, led by Ahmed and his allies.

A massive privatisation programme of state-owned telecoms, energy, shipping and sugar industries is in the works, along with changes to the existing grade structure of the education system and the introduction of high university tuition fees for the first time. Rekiso says the programme appears to be similar to “disastrous” reforms imposed on many African countries in the early 1980s by international economic institutions such as the International Monetary Fund.

Indeed, the IMF has made no secret of its desire to see Ethiopia liberalise its economy. In a December 2018 report, fund economists warned that the limits of the current ‘development phase’ could be being reached, with an increasing public debt burden and ‘external imbalances’ threatening to derail progress.

The looming forces of international institutions are poised to exert their influence on Ethiopia’s economy, seemingly aided by Ahmed, who will go to the polls under the ‘Prosperity’ banner for the first time this year. The result is that the future of public spending – including on education – remains uncertain.

The prevailing orthodoxy in Ethiopia – where the government pushes to raise quantity, even at the cost of quality – has laid foundations for economic transformation, but they are flimsy. The economy is yet to feel the full effect of an educated population meeting its potential in the workplace, despite the undisputed successes in reducing poverty rates.

Policy needs balance. Workers need jobs that match their skills. Society benefits when people are empowered to take opportunities, but only as long as those opportunities exist.

For Ethiopia, the second-largest country in Africa by population, to make good on its promise for a brighter future, the government will need to evolve its approach to education further.

But it must not abandon the commitment the country’s leaders have shown for the past three decades to giving Ethiopians the tools to improve their lives and transform their country.