South-Sudan-shutterstock_326255036.jpg

The world's poorest nations, like South Sudan, have become further locked into poverty as a result of the commodity price crash and faltering international support, according to the United Nations.

In a report on the progress of the world’s least developed countries (LDCs), published yesterday, the United Nations warned that a drop in international support also means these countries are likely to remain locked in poverty.

It predicted the world will miss its target to halve the size of the LDC group by the end of the decade. The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, which were agreed by world leaders last year and include targets on ending extreme poverty, are also at risk.

“These are the countries where the global battle for poverty eradication will be won or lost,” said Mukhisa Kituyi, secretary general of the UN Conference on Trade and Development, which produced the report.

“A year ago, the global community pledged to ‘leave no one behind’, but that is exactly what is happening to the LDCs.”

Global poverty is increasingly concentrated in the 48 LDCs, which comprises mostly of African and Asian nations alongside some Pacific island states and Haiti.

Many of the LDCs remain trapped in commodity dependency. Last year, when oil prices plunged by 47.2%, which was followed by many other commodities following suit, LDC economies were hit hard.

Real gross domestic product growth across the group dropped to 3.6% – its lowest level since 1995 and well below the 7% targeted. Living standards, measured in terms of per capita income, declined in 13 of the LDCs, in three cases by more than 10% (Yemen, Sierra Leone and Equatorial Guinea).

Outbreaks of diseases like Ebola, or conflicts, were key factors in some of the LDCs’ decline. However, UNCTAD said that the collapse in commodity prices played a strong role in knocking back the group as a whole.

It described the LDCs’ commodity dependence as one of three “major vicious circles” holding the group back.

Commodities accounted for more than two thirds of the merchandise exports between 2013 and 2015 in 38 nations in the group, with many locked into specialising in primary commodities and low-value added products.

“Commodity dependence increases vulnerability to exogenous shocks (such as adverse terms of trade movements, extreme meteorological events and climate change,” the report said.

“It also often gives rise to a ‘natural resource curse’, when exchange rate appreciation undermines the competitiveness of the manufacturing sector or when rent-seeking behaviour prevails, and there are limited incentives to invest... even in human capital.”

UNCTAD said commodity dependence tends to be difficult to break out of, with only a few LDC’s – Uganda, Afghanistan, Burundi, the Comoros and Solomon Islands – significantly reducing dependence since the beginning of the century.

The group also remains stuck in a “poverty trap”, where low income and limited economic growth leads to high levels of poverty. Poor nutrition and health, a lack of education and undermined productivity and investment then in turn block future growth.

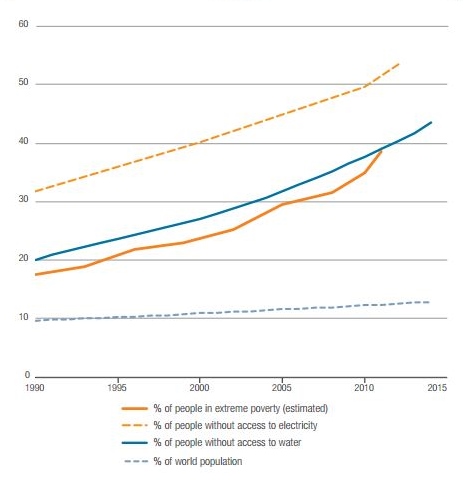

UNCTAD noted that it is in LDCs where poverty “has been and remains most pervasive”. The proportion of the global poor in the LDCs has more than doubled since 1990, to well over 40%. They also account for the majority of people in the world without access to water (43.5%) and electricity (53.4%) – figures that have risen dramatically in the past two decades.

ldcs.jpg

LDC's share in world population's extreme poverty and lack of access to water and electricity. Source: UNCTAD based on data from the World Bank and PovcalNet database.

In six of the LDCs, the rate of poverty is between 70% and 80%, and in a further 10 it is between 50% and 70%. There are only four other countries in the world where the rate is above 30%.

The report concluded that faltering international support means that only 10 of the LDCs will “graduate” from that status by 2020 – a number that would need to more than double in order to meet the target to halve the size of the group.

Yet many of those that will graduate are unlikely to achieve the deep-seated changes needed to maintain the momentum of graduation and progress further without support in finance, trade and technology, it added.

“Graduation... is the first milestone in the marathon of sustainable long-term development,” said Kituyi. “So how a country graduates is just as important as when it graduates.”