web_angola_istock_29726080_large.jpg

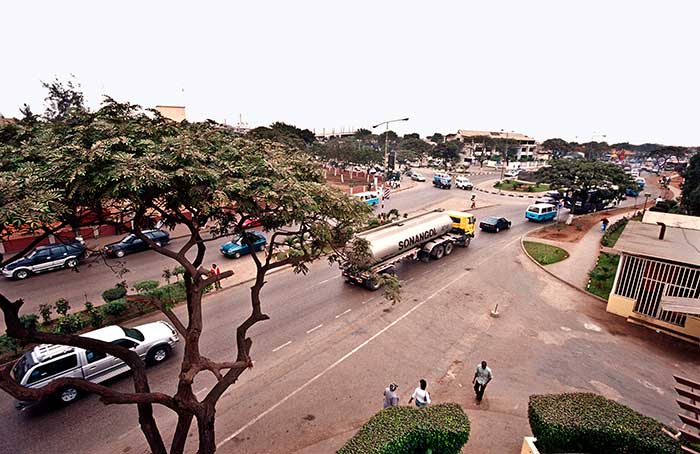

A truck from Angola's main oil company Sonangol. The crash in commodity prices, and subsequent decline in the oil-reliant government's revenues, saw the country spend almost half of its income on debt repayments last year - more than any other developing country.

The campaign group said yesterday that falling revenues, a borrowing boom and the rising value of the US dollar meant developing nations saw almost 50% more of their revenues tied up in debt costs than just three years ago.

It warned that with the US Federal Reserve set to raise interest rates imminently, debt payments will be further pushed upward.

Tim Jones, economist at the Jubilee Debt Campaign, said this is putting pressure on government budgets, precisely when more spending is needed to meet the Sustainable Development Goals – estimated to come with a price tag of as much as a trillion dollars per year.

Figures published yesterday by the campaign group showed that those most affected by rising debt are nations that have been on the short end of global events in recent years: commodity exporters, hit by the crash in prices; Arab nations shouldering the refugee burden from the crisis in Syria; and small island states hit by hurricanes.

Angola, Africa’s biggest oil exporter, for instance, spent 44% of its government revenues on debt in 2016 – the highest of any country. It was followed closely by Lebanon, where refugees now make up a quarter of the population, at 42%.

Other nations that made the top twenty included: Jordan (17.5%), also a major refugee hosting nation; Mozambique (20.2%), in the midst of a debt crisis; and Grenada (23.5%), where debt started piling up after hurricanes in 2004 and 2005.

The campaign noted that Grenada, along with Jamaica and the Dominican Republic – also on the list – were once considered too rich to benefit from significant debt relief initiatives such as the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative.

Initiatives like the HIPC, launched in 1996, worked to ease some of the poorest countries’ unsustainable debt burdens. However after a period of relief, observers have noted that debt in developing nations is once again starting to pile up at a concerning rate.

This has in part been fuelled by low interest rates in western countries, which have driven a large increase in lending to their poorer counterparts. External loans to low- and middle-income nations have more than quadrupled since 2008, from $56bn then to $262bn in 2016.

In mid-2014, commodity prices collapsed, decimating a key source of revenue for many developing countries whose economies depend on exporting such materials. This also triggered a decline in the value of such countries’ currencies, compounding a simultaneous rise in the value of the US dollar – the currency most debts are owed in.

These factors meant the relative size of countries’ debt repayments grew. As a result countries on average spent 9.7% of their revenues on debt – a 45% increase since 2014. Any future interest rate increases by the US Federal Reserve will mean they have to pay even more.

Jones said that in such situations, financial aid from lenders of last resort, such as the International Monetary Fund, will only serve to exacerbate the issue.

“The danger is the IMF and other loans will bail out reckless lenders, increasing debt burdens, and leading to years of economic stagnation, just as in Greece,” he warned.

Mozambique, for instance, has fallen into a debt crisis after it was discovered that two London banks, Credit Suisse and VTB Capital, had secretly lent $1.1bn to two companies in the country, with government guarantees.

The loans were never publicly declared, agreed by the Mozambique parliament as per the law or disclosed to the IMF, which subsequently suspended financial aid to Mozambique. Other donors also put their funds, which the country heavily relies upon for revenues, on hold.

Jones said that instead of bail outs, “reckless lenders should be made to shoulder some of the costs of recent economic shocks by accepting lower payments”.