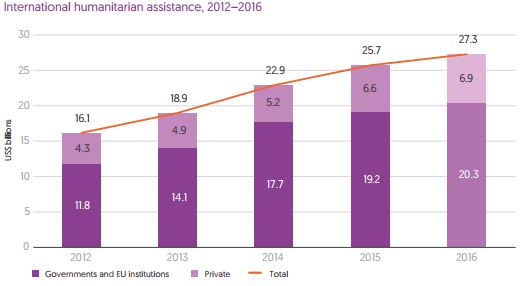

This year’s Global Humanitarian Assistance report, published today by Development Initiatives (DI), showed that although total humanitarian aid rose to a record high of $27.3bn in 2016 – $1.5bn more than in 2015 – this 6% increase was significantly lower than the 12% seen in 2015, the 21% seen in 2014 and the 18% seen in 2013.

iha_gha.jpg

Data analysis and figure development by Development Initiatives: www.devinit.org

One factor in this decline was a 24% decrease in funding from Middle Eastern nations such as Kuwait, which reduced its contributions by 50%.

However DI said 2016’s slower-onset emergencies, including ongoing conflicts, worsening food crises and extreme weather, did not mobilise as much attention as the sudden and dramatic crises of 2015, such as Ebola or the Nepalese earthquake.

Need, however, is rising. The report estimates that over 164 million people across 47 countries were in need of aid last year – a record high. Over a quarter of these were concentrated in three countries: Yemen (21.2 million), Syria (13.5 million) and Iraq (10.4 million).

With demand far outpacing resources and those relying on aid often dissatisfied, last year the UN organised a landmark summit aimed at reforming the system. This year’s GHA is the first annual stock take of humanitarian efforts since.

It shows that as well as keeping pace with need, donors and aid organisations have some way to go in keeping the commitments made at the World Humanitarian Summit (WHS) last May.

One of those commitments – which the world’s major donors and NGOs signed up to in a document called the Grand Bargain – was to better harmonise humanitarian and development work.

“Poverty, crisis and risk are intrinsically linked,” explained Harpinder Collacott, executive director at DI. “An estimated 87% of people living in extreme poverty that are considered environmentally vulnerable, fragile or both.”

This means that attempting to prevent and prepare for crises, as well as responding to them, is critical.

An opportunity to better link these two separate streams of aid work is found in the delivery of multi-year plans and funding, which is also useful when crises are ongoing and protracted.

However the report found that most UN-coordinated response plans are still single-year, and renewed annually.

The number of multi-year plans fell to just five in 2016, down from 13 in 2014. No “major collective shift” towards multi-year funding is yet apparent either, the GHA said.

Other commitments towards better efficiency, flexibility and transparency in humanitarian financing are also a long way from being met.

Delivering more funds directly to local and national responders – who are often on the front lines, especially in the immediate aftermath of an emergency – is one of these.

This is more efficient than the current system, where funds are often channelled through large international bodies down through a chain of progressively smaller organisations, with everyone skimming some off on the way.

The Grand Bargain calls for at least 25% of all aid funding to be delivered in this way; in 2016, the number stood at 2%.

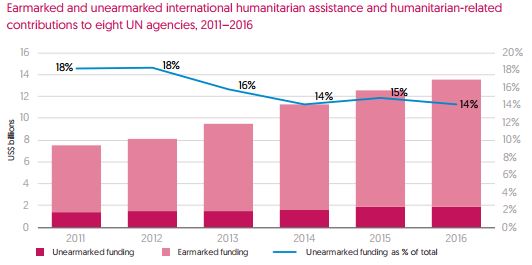

At the WHS, the aid community also agreed funds need to be more flexible, allowing resources to be allocated to changing needs.

While on the one hand this is improving, with donors channelling more money through pooled funds, they are also increasingly earmarking their other contributions. Since hitting a high of 18% of total aid in 2011, unearmarked contributions have stagnated since 2014.

earmarks_gha.jpg

Data analysis and figure development by Development Initiatives: www.devinit.org

In order to leverage all available resources, donors are increasingly turning to different funding mechanisms rather than relying on grants alone. Innovative instruments like risk insurance, or impact bonds are on the rise.

Collacott said such a “holistic set” of financing tools is critical to dealing with the causes and consequences of crises, but that greater transparency is needed to understand what resources are available and maximise their effectiveness.

More accurate estimates of the funding available and how it is channelled towards those in need would reveal deficits and inefficiencies. Many aid organisations and donors are already signed up to transparency initiatives, with frequently cited benefits including improved monitoring, accountability and external communication on the impact of their work.