web_parliament_building_lisbon_istock-511647879.png

Parliament building in Lisbon

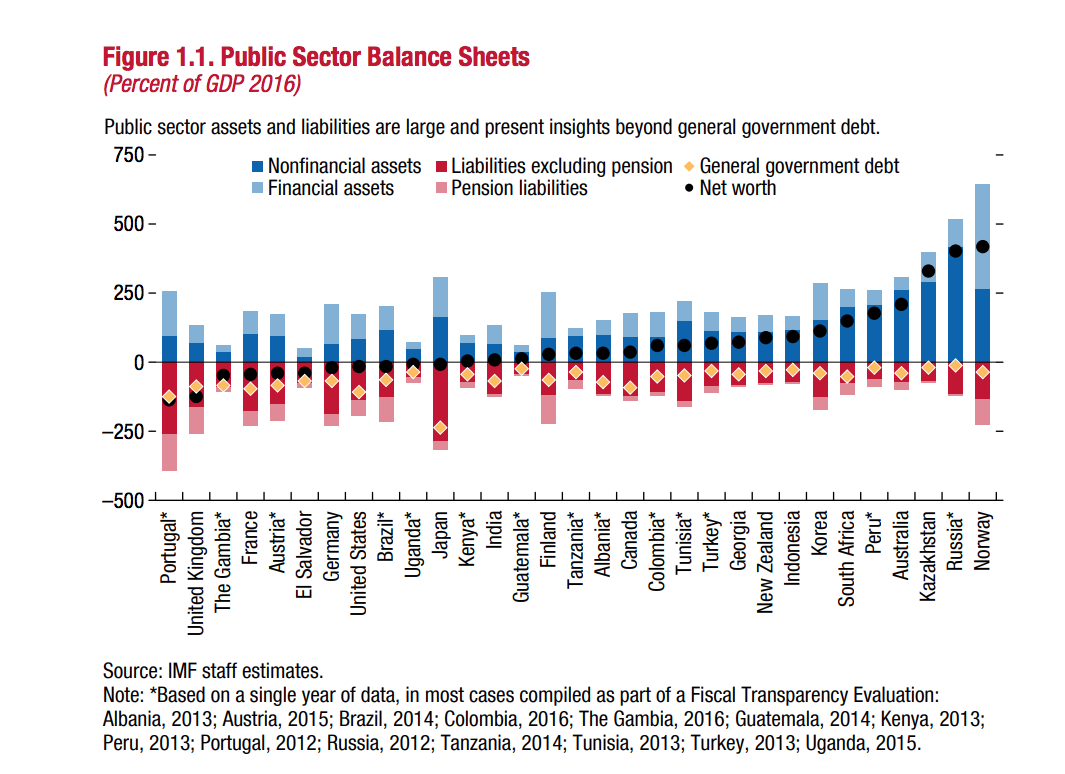

At the top of the rankings was Norway, with the most secure public finances because of its oil wealth. Russia, Kazakhstan and Australia followed in the rankings.

See the graph from the fiscal monitor Managing Public Wealth below.

Portugal’s public finances were found to be the worse, in the latest fiscal monitor, which examined the assets and liabilities – the balance sheet – of 31 countries, which cover 61% of global GDP.

The IMF said it chose to examine balance sheets in the latest monitor - rather than just debts and deficities - because it gave a “broader fiscal picture”.

On Portugal, Abdelhak Senhadji, the deputy director of the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department, told PF International the country’s negative net worth – which stands at -135% of GDP - is mainly a result of large pension liabilities, which at the end of 2012 were around 133% of GDP.

Almost £1 trillion had been wiped off the wealth of the UK’s public sector since the financial crisis, the report, released in Bali last week, showed, putting it in the second weakest position of the 31 nations assessed.

Countries such as Gambia, Uganda and Kenya ranked above the UK because they have higher net wealth relative to GDP, despite their smaller assets and liabilities, it added.

China’s public wealth had deteriorated to about 8% of GDP, with losses to pension funds and non-financial assets as a key reason for this.

Although, Norway’s fiscal position is “very strong”, the report noted, “long-term spending pressures significantly reduce its intertemporal net worth relative to its vast asset position”.

Finland, on the other hand, the IMF added, had recently planned and carried out reforms that “mean that future primary balances are positive despite an ageing population, adding to intertemporal net worth”. Finland’s public finances strength was ranked in the middle of the 31 countries in the monitor.

The Washington-based lender assessed the total assets of the 31 countries as worth $101 trillion, or 219% of GDP. Although, it added: ‘Recognising these assets does not negate the vulnerabilities associated with the standard measure of general government debt, comprising 94% for these countries”.

The net worth – the difference between assets and liabilities – also does not take future tax intake into consideration, it added.

The IMF uses different methodolgy in its fiscal monitors, released in the spring and autumn ever year.

It emphasised the importance of balance sheets in the latest release, saying: “Once governments understand the size and nature of public assets, they can start managing them more effectively. ”

Good public sector balance sheets were key if governments wanted a full picture of their public finances and to prepare for any future financial crash, it said.

It highlighted countries with strong balance sheets – accounting for their assets and liabilities – experience “shallower and shorter” recessions than those without.

Vitor Gasper, director of the fund’s fiscal affairs department, said at a press conference last week: “It is time to build fiscal space against the next downturn.

“Systematic compilation of use of public sector balance sheets can lead to lower debt servicing costs and higher return on assets, better management of risks.

“And, overall, it may help to put public wealth to work at the service of societies' economic and social goals.”

Manj Kalar, international public finance management consultant, said of the methodology: “The IMF public sector balance sheet analysis report should be commended for shining a light on public sector assets and liabilities.

“Traditionally the focus has been on measuring public sector debt as a proportion of GDP.

“That’s not the whole picture. To get a complete picture you need to focus on assets too - to assess how to better manage assets, and achieve better public financial management.”

Alan Wheatley, associate fellow at Chatham House's Global Economy and Finance department, said that the report help draw attention to two things.

“First, by optimising the management of public sector assets, governments can considerably improve revenues.

“Second, with their populations ageing fast, governments need to get serious about making plans to fund future public-sector pension liabilities.”

But he added: “Flogging the family silver - no matter how big the hoard of public sector assets - is a one-off palliative and not a lasting remedy.”