Accountants are often thought of as the boring type. Some may think of us as mere bookkeepers.

Whilst that may be true of some of us, the way we record transactions can have a profound impact on human behaviour.

An important accounting metric for evaluating the performance of government entities is revenues minus expenditure, the revenue surplus / deficit.

An entity constantly incurring deficits is not in a position to sustain its operations in the long term. At some point, creditors will not finance the deficit, resulting in a crisis.

Consequently, there are great incentives to overstate revenues and understate expenses.

One recent instance is the pay-as-you-go accounting for pensions.

Since pension liabilities were not recognised as expenses when incurred, politicians were happy to promise greater benefits, as there was no immediate impact on the budget deficit.

The consequence was a ballooning of unrecognised pension liabilities.

Many countries have moved to defined contribution pensions in recognition of the skewed incentives to understate pension liabilities.

Goa Foundation (GF), a non-profit in India, has pointed out in a note and a subsequent response to FAQs, that a similar anomaly, perhaps larger, is created by the treatment of mineral receipts.

IMF’s Government Finance Statistics Manual 2014 treats mineral receipts as property income, specifically rents. Most accountants would agree minerals are a shared inheritance, akin to family gold.

Royalties are clearly the consideration for the sale of the minerals, a capital receipt. The accounting needs changing.

The impact is two-fold.

First, mineral receipts are treated as revenue. More revenues are good. This incentivises mining till nothing is left – see Nauru.

Second, minerals are being sold for much less than its true value.

IMF estimates that the best case is a 10% loss in value for oil, and 35% for minerals. In iron ore mining in Goa, over an 8 year period, the loss is estimated at over 95% of the economic rent (sale price minus all expenses and a generous profit). Since mineral receipts are treated as revenue, the loss in asset value is not recognised. This incentivises crony capitalism.

The table below illustrates how Goa’s public finances would change with appropriate accounting for mineral receipts.

Amounts in Rs. billion | ||||

Aggregate | As Reported | In Reality | ||

Transaction narrative |

Revenue (mining) |

23.87 | Opening capital : mineral Mineral sold Capital receipt : cash Change in net worth : loss Closing capital : cash | 516.55 -516.55 +23.87 -492.68 23.87 |

Revenue | 274.02 | Actual revenue Reported revenue Less: mineral receipts | 250.15 274.02 -23.87 | |

Expenditure | 320.08 | Actual expenditure Reported expense Add: Loss from mining | 812.76 320.08 492.68 | |

Deficit | 46.06 | 562.51 | ||

Goa GDP | 1,872.97 | (Subtracting the economic rent) | 1,356.42 | |

Transaction narrative As % of GDP |

Revenue (mining) |

1.27% | Mineral sold Capital receipt : cash Change in net worth : loss | 38.08% 1.76% 36.32% |

Deficit as % of GDP | 2.46% | 41.47% | ||

Mineral receipts are reported at merely 8% of government revenues, and 1.3% of GDP. Yet this innocuous item hides a catastrophe.

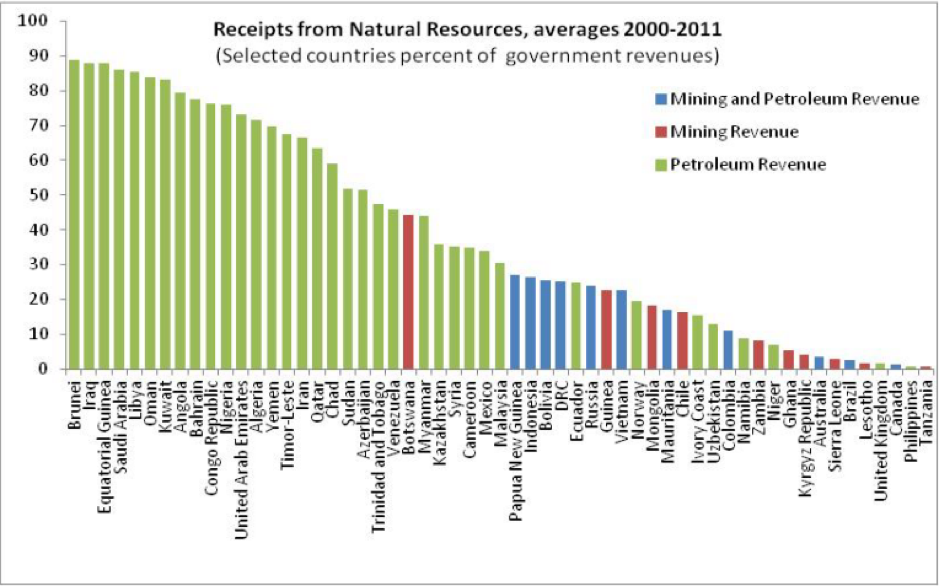

This problem is widespread. Examine the chart below from the IMF:

The accounting treatment is driving perverse incentives. Politicians argue for new mines or increased extraction on the grounds of a boost to the government revenues.

Since mineral receipts are accounted for as revenues, a derived goal is to maximise revenues, a fuzzy target. This drives increased extraction at lower prices, large losses, wasteful spending, declining wealth and increasing inequality.

The distressed sale of minerals incentivises rapid mining and exit. The people on the ground and the environment are obstacles between the miner and great wealth. Often they resist, resulting in conflict and civil wars.

The commodity cycle exacerbates the problem. Government “revenue” rises when commodities boom, and expenditure does too – politicians know spending more leads to re-election. When prices crash, there are three painful choices – cut expenditure, raise taxes, or sell more minerals. Look at Venezuela. Or Alaska for a developed nation example.

If politicians had to recognise that they are selling the family gold, significant losses would be politically untenable. This would squeeze the corruption and crony capitalism.

Arguments for consuming the capital would be difficult. Consequently, the savings rate is likely to rise, leading to further growth.

Some countries on this chart have recognised the problem. Botswana explicitly targets its non-mineral budget deficit.

Similarly Norway saves all its oil receipts in its famous fund, while only allowing the real income from the fund to be treated as revenue.

However, the permanent solution is a simple change to IMF’s Government Finance Statistics Manual 2014. Will they?