The world’s newest migration crisis is unfolding in Latin America, where Venezuela’s economic collapse and unprecedented humanitarian crisis has sparked a wave of emigration to neighbouring countries.

While these countries are providing helpful support to migrants in many areas, large migration flows have strained public services and labour markets in these countries.

According to the Response for Venezuelans, which is a joint International Organization for Migration and UNHCR platform, the total number of migrants leaving Venezuela reached about 4.6 million in November 2019—with about 3.8 million settled in Latin America and the Caribbean.

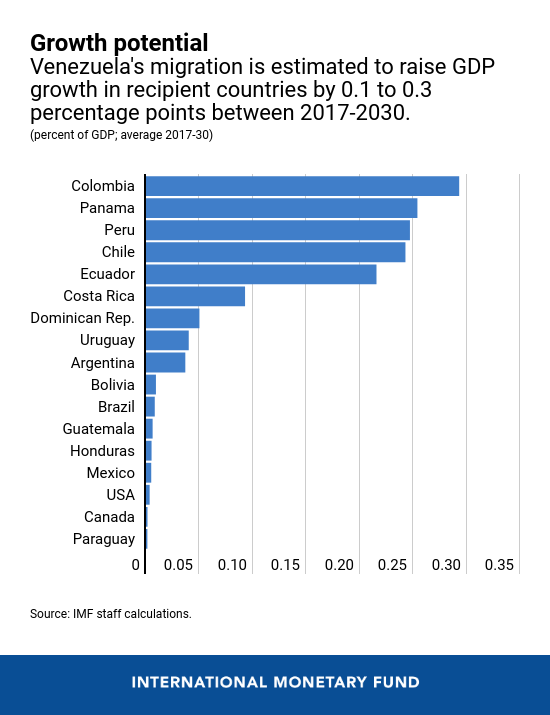

Venezuela’s migration can potentially raise GDP growth in receiving countries.

Without a clear end in sight to the crisis and amid rising social tensions across the region, how can Latin American governments best craft a coordinated response that serves the needs of refugees while protecting their citizens and economies?

Striking this balance will be critical, but also potentially beneficial.

Our latest research finds that Venezuela’s migration can potentially raise GDP growth in receiving countries by 0.1 to 0.3 percentage points during 2017–2030.

Policies, including greater support for education and integration into the workforce, could help migrants find better-paying jobs and, ultimately, help raise growth prospects for countries receiving migrants.

Crisis and Exodus

Since the beginning of the crisis, living conditions have severely deteriorated for Venezuela’s 31 million inhabitants. Extreme poverty rose from 10% of the population in 2014 to 85% in 2018. And severe shortages of food and medicines continue to plague the population.

Making matters worse is the sharp drop in economic activity, which has contracted by around 65% between 2013 and 2019. This was driven by plummeting oil production, worsening conditions in other sectors, and pervasive electricity blackouts.

Meanwhile, hyperinflation continues unabated with monthly price increases of about 100 percent, rivalling other historic hyperinflation episodes.

Facing these harsh living and economic conditions, migrants are fleeing Venezuela and settling in neighbouring countries.

Colombia has received the largest share, followed by Peru, Ecuador, Chile, and Brazil. Migration flows to some countries in the Caribbean and Central America have been even larger relative to their local populations, though smaller in absolute numbers.

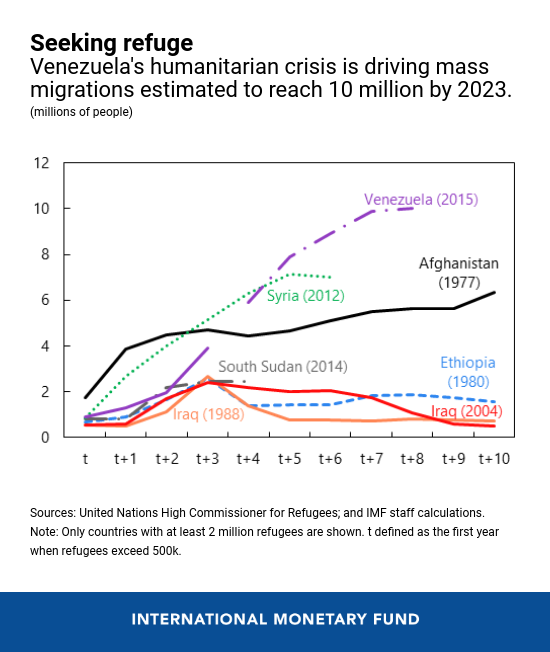

Based on current trends, our research projects that the total number of migrants could reach 10 million in 2023—although with a wide range of uncertainty around this figure. If realised, Venezuela’s mass migration would overtake past refugee crises—for instance, Syria in the 2010s or Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Regional spillovers

What does an exodus of this scale imply for the region? Spillovers from large migration flows from Venezuela are expected to place immediate pressures on fiscal spending and labour markets in recipient economies, but over time they would also contribute to higher economic growth.

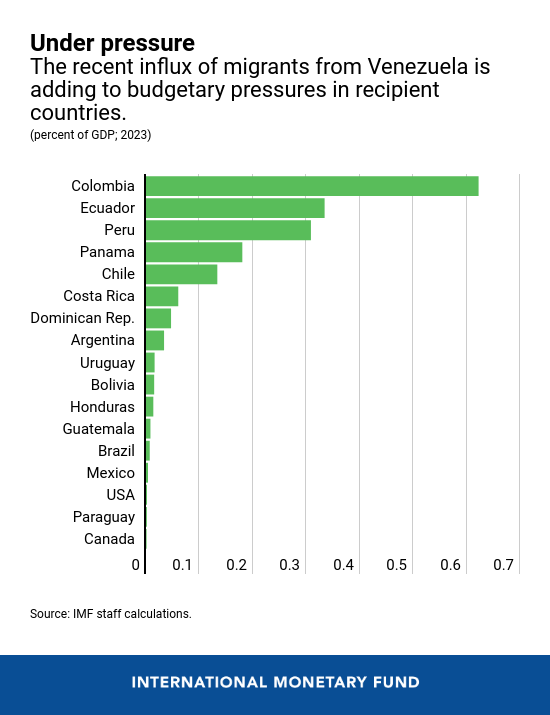

On budgetary pressures, receiving nations are providing helpful support to migrants in the form of humanitarian aid, basic healthcare, education, validation of educational titles, and job search.

Using detailed data for Colombia on each of these categories as a benchmark, estimates suggest that public spending related to growing migrant populations could reach around 0.6% of GDP in Colombia by 2023, 0.3% in Ecuador and Peru, and 0.1% in Chile.

The overall impact on the fiscal deficit would be smaller than what the higher spending would imply, because tax revenue would also increase as the economy expands.

Over time, real GDP growth is expected to increase as the size and skills of the labour force expand, as many Venezuelan migrants bring relatively high levels of education and skills.

Factors such as language and culture may also help migrants from Venezuela integrate more easily into regional economies in Latin America compared to other recent migration episodes. The expansion of the labour force would also lead to higher investment.

In the near term, however, the influx of migrants—depending on the speed and scale of the inflows—can place pressure on labour markets to absorb them, displace some local workers, and increase informality.

Taking into account the age, size, and skill levels of migrants, as well as the fact that most have taken low-skilled jobs in the informal sector, Venezuela’s migration is estimated to raise GDP growth in recipient countries by 0.1 to 0.3 percentage points during 2017–2030.

The growth impact could be larger and more immediate if migrants can find jobs in line with their educational level—a transition that can be made easier by policies.

Policy Challenges

A key challenge for policymakers in the region is how to manage the transition at a time when their economies have slowed, and many countries need to reduce their fiscal deficits

In the near term, facilitating the integration of migrants into the domestic labor market and easing the process to validate their professional titles or to set up businesses would maximize the impact on growth and minimize the need for public support.

Multilaterally, international cooperation to assist the main receptors of Venezuelan migrants with the costs of migrant assistance should be considered. Individual country actions toward migrants, such as border restrictions, can complicate the situation for other partners—pointing to the need for a more regional approach.

Looking further ahead, providing migrants with access to education and healthcare will be key to ensuring they live long and productively to benefit not only themselves but also the economies in which they reside.