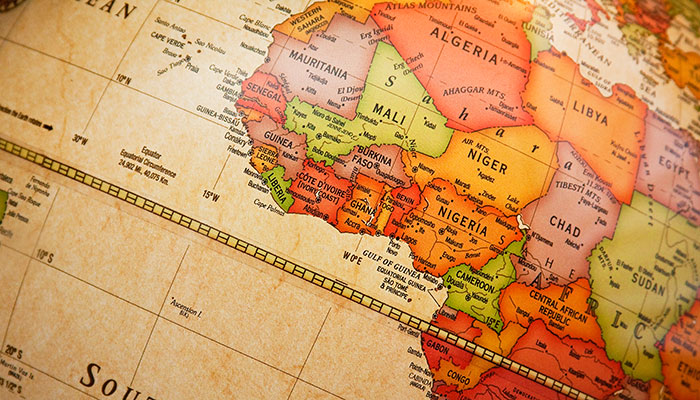

IMF support for the continent has been unprecedented: since the beginning of April help has exceeded $13bn, not including a $5.2bn stand-by agreement recently made with Egypt, involving 31 of Africa’s 54 countries.

Recent beneficiaries have included Guinea ($148m), Rwanda ($220.5m) and Liberia ($50m), while the largest packages have been agreed with Egypt ($2.77bn), Ghana ($1bn) and the Ivory Coast ($886m).

And at least two more countries – Zambia and Cameroon – are in talks with the fund to discuss support.

Specific measures include cash transfers, loans and debt relief, and most of the Covid-19 packages do not come with as many strict requirements to enact reforms as normal IMF programmes do, because they have been needed so quickly.

But this does not mean the funding will come without scrutiny, IMF communications director Gerry Rice told reporters.

“While there is less scope for attaching our traditional conditions, we are working on measures to promote transparency and accountability, and ensure that IMF resources are used for their intended purposes,” he said.

“We’ve been using this phrase: ‘Keep the receipts. Spend the money as needed to protect people and livelihoods but keep the receipts of the emergency financing’. That means they can ensure proper accountability, transparency and use of funds.”

Sub-Saharan Africa was named the most corrupt region in the world by Transparency International in its 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index it released in January.

Of the bottom 50 countries in the world, 25 were in the region, including the lowest scorer Somalia.

The emergency financing from the IMF will be subject to independent audits, Rice said, and the fund will be supporting and advising countries on their reporting.