The need to do more with less always tests austerity policies – but in Mexico this conundrum has been exacerbated by a populist reflex towards migration north of the border.

Central American migrants heading for the US have forced left-of-centre president Andrés Manuel López Obrador into rolling back a pledge to slash spending after years of government waste.

Buckling under pressure to follow Donald Trump’s anti-migrant agenda, Mexico’s experience exemplifies how fiscal discipline – and progressive aspirations – can fall prey to politics.

Migration has become a flashpoint in US-Mexico relations – apprehensions at the frontier could hit 1 million this year – with Trump forcing López Obrador to curb his humanitarian instincts and stress tough border enforcement.

While experts suggest that reversing cuts may ultimately allow Mexico to reorientate migration policy positively, this is unlikely during Trump’s tenure.

Ariel Ruiz Soto, associate policy analyst at the Washington-based Migration Policy Institute, says: “López Obrador came to power with a strong message of austerity, limiting government spending and ending corruption, and that affected the budgets of INM, Mexico’s immigration control agency, and Comar, the asylum agency, which, instead of increasing, decreased.”

'The Americans love Mexican workers, but don’t want families. They know how to manage Mexican migration, but not Central American migration.'

Jorge Durand Arp-Nisen, co-director of the Mexican Migration Project

Over the summer, however, Mexico’s foreign minister reversed this position by signalling that cuts to migration agencies would be eased.

“The Mexican administration came in with a very idealistic perspective of what it could do – given Mexico’s history of migration – but it has been derailed by pressure from the US.”

Emigration from Mexico to the US has halved in the past decade, while migration from the ‘Northern Triangle’ – Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador – has surged.

As a result, asylum claims in Mexico have soared, with applications increasing by 196% this year.

This has overwhelmed Comar – in June, the agency had just 48 staff members yet it expects at least 60,000 asylum claims this year. With an annual budget of just $1.2m, its director has pleaded for help.

The Migration Policy Institute identifies factors that ‘push’ migrants to leave Central America – including poverty, climate change, violence and instability – and factors in the US that ‘pull’ them, such as family connections and jobs.

A shift from labour to family migration is under way. In 2008, MPI noted that 90% of border apprehensions were of Mexican citizens. But, by 2019, 74% were of Guatemalans, Hondurans and Salvadorans, with two-thirds of these being families or unaccompanied children.

A shift from labour to family migration is under way. In 2008, MPI noted that 90% of border apprehensions were of Mexican citizens. But, by 2019, 74% were of Guatemalans, Hondurans and Salvadorans, with two-thirds of these being families or unaccompanied children.

Jorge Durand Arp-Nisen, co-director of the Mexican Migration Project, an initiative by Guadalajara and Princeton universities, says: “The Americans love Mexican workers, but don’t want families. They know how to manage Mexican migration, but not Central American migration.”

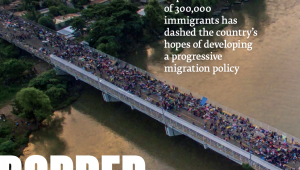

The US immigration system has failed to adapt, hardening rhetoric on the populist right. In July, Trump announced an ‘expedited removal’, under which 300,000 immigrants face rapid deportation. Using the threat of tariffs, he has imposed new ‘agreements’ on Mexico and Guatemala, requiring them to host asylum seekers.

Under López Obrador, there were high hopes for a shift in policy emphasis, based on a new humanitarian visa to regularise the stay of migrants in transit. However, Trump’s priorities have prevailed.

This year, the US announced the controversial ‘Remain in Mexico’ policy, requiring migrants with asylum claims to wait in Mexico while their cases are processed in the US – which can take years. It also forced its southern neighbour to beef up enforcement under the threat of tariffs.

The US has since ruled that those crossing the border are ineligible for asylum if they have not previously applied in transit countries, and reports suggest that Trump is now considering halting refugee programmes entirely.

Mexico’s willingness to get tough has come at a political cost.

Durand says: “Many people think the reaction by López Obrador and foreign secretary Marcelo Ebrard was too fast.

“They didn’t have any time to think about the implications of making 3,000 members of the National Guard work as migration officers, which they are not trained to do.”

A key issue now facing Mexico is how to finance this new normal – Trump’s June deal did not include any cash and will increase pressure on public spending.

Comar’s budget was cut this year to 21m pesos ($1.07m), 6m pesos below 2018, and INM’s was reduced by 23% with the loss of 720 jobs. In the first four months, INM reportedly spent 50% (about $11m) more than the $20m approved. Estimates suggest that overspending on migration will hit 875m pesos ($45m) this year.

In June, Ebrard signalled a policy reversal, without going into detail, saying that INM staffing was being reinforced. Leaders of the ruling Morena party, meanwhile, indicated that they expected “a significant increase” in the migration budget.

However, one thing seems clear – Trump will not bail out Mexico.

MPI’s Ruiz Soto says: “Despite the current migration protection protocols known as ‘Remain in Mexico’, the US is not giving Mexico any money for housing, programmes or services to actually have migrants be willing to stay on the Mexican side of the border for the long term.”

It is precisely these fiscal strains, caused by sudden migration flows, that have prompted the Inter-American Development Bank to act, albeit not in Mexico.

In May, the IDB approved access to a special grant facility for countries in South and Central America – particularly Colombia, Ecuador, Chile and Peru, which are receiving large inflows from Venezuela (see panel), but also Belize and Costa Rica.

This provides $100m in grants to be combined with existing loans to improve access for both migrant and host communities to housing and healthcare.

Antoni Estevadeordal, a special adviser at the IDB, coordinates the initiative at the head of a taskforce responding to sudden migration flows.

Antoni Estevadeordal, a special adviser at the IDB, coordinates the initiative at the head of a taskforce responding to sudden migration flows.

He says: “Over time, migrants can help make communities more dynamic and prosperous. However, if not adequately managed in the short term, these inflows can strain public services and fiscal budgets, impact labour markets, and generate political tensions.

“Our plan is to start making very rapid interventions in the most pressured countries in the next two or three years to deal with these shocks and the immediate needs that the countries have in terms of absorbing this type of pressure.”

Analysts agree that reducing undocumented migration requires long-term development.

Arguments for the positive contribution of migration to development are well rehearsed, but Mexico faces difficulties leveraging it to fill labour shortages.

Ruiz Soto says: “This is part of a bigger question about why migrants are generally not electing to stay in Mexico.”A key problem is Mexico’s minimum wage. Research by Durand shows that, in most cases, this is lower than in Central America, and far below that of the US.

Although the US prefers bilateral solutions, there is a multilateral framework for addressing migration in Latin America.

Estevadeordal says: “This is a larger development question and it is why our initiative is focused on recipient countries: the bank has invested a lot across the board in these countries – not only to avoid migration but to support their long-term development strategies for infrastructure, security, and competitiveness.”

López Obrador and his Central American peers are sketching out plans with the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean to recast migration as a development issue. This involves an ambitious $30bn comprehensive development plan, but details are sketchy.

Ruiz Soto says: “It is certainly a good plan. It’s a good incentive, and they have the right approach, but I think we should all have a healthy level of scepticism about how practical it is in the short-term.

“It just doesn’t seem like there is a way out without the US participating, yet it is counter to the current narrative of the Trump administration.” Mexico is struggling to get the US administration to live up to existing promises of $5.8bn in loan guarantees for regional development.

While the crisis offers opportunities to retool migration systems for the future, it also requires a regional approach – something Durand says is unlikely with Trump in office. “There is a regional solution, but it’s almost impossible to work with Trump.”

Exodus stokes fiscal crisis

The humanitarian crisis that has engulfed Venezuela demonstrates the close links between economic turmoil and migration. A staggering four million Venezuelans have left their country since 2015, according to UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and the International Organization for Migration.

While headlines have concentrated on the human costs of this disaster – caused by confrontation between the socialist government and the US-backed rightwing opposition – the fiscal implications are enormous. According to the International Monetary Fund, real GDP could fall by 35% in Venezuela this year, bringing the estimated cumulative decline since 2013 to 60%. In turn, migration is expected to surpass five million by the end of 2019.

Latin American countries are hosting the vast majority of Venezuelans, with Colombia accounting for 1.3 million, Peru 768,000, Chile 288,000, and Ecuador 263,000. However, many have travelled to Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

These sudden inflows come at a fiscal cost. Antoni Estevadeordal, a special adviser at the Inter-American Development Bank – which has stepped in to provide help – said it is assessing the impact of migration shocks on the public finances of affected countries. It is estimated, for example, that between 0.5% and 1% of GDP is being spent by some of Venezuela’s neighbours to cope with the influx.

In Colombia, the IMF estimates that humanitarian support such as healthcare and education could cost about 0.5% of GDP this year, although this will decline to 0.1% by 2024 as migrants integrate.

Estevadeordal said: “Countries like Colombia and Ecuador that have experienced the effects of the Venezuelan migration shock have been very welcoming in terms of providing very specific types of regulatory provisions, temporary permits and other creative means to accommodate this population.

“What we are trying to do is provide the infrastructure they need to support the policy choices that they make, so these populations can become fully fledged contributors.”

Colombia demonstrates that migration also offers a development opportunity. The IMF has said that Venezuelan migration is likely to contribute to a rise in growth in Colombia to 3.6% this year and next as migrants fuel demand for services.

Under current trends, Venezuelan migration is projected to hit 2.5 million in Colombia by the end of 2020. But the IMF says that, if this figure doubled, it could further increase potential GDP growth by an additional half a percentage point.