Rookie UK chancellor Rishi Sunak last month garnered praise for his polished performance delivering his maiden Budget to the House of Commons. However, during just over an hour at the dispatch box, Sunak failed to mention one eagerly awaited policy announcement. Keen public finance watchers had to turn to documents published alongside the speech to discover the Treasury was planning to push ahead with its plans to introduce a digital services tax.

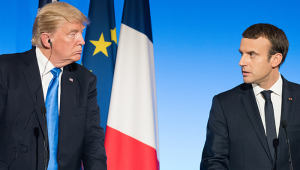

Sunak’s reticence was, perhaps, understandable. The topic of imposing extra tariffs on profits made by the world’s largest internet companies is one of the most sensitive in current international tax relations. Earlier this year, France agreed to suspend its own digital tax after a row with the US on the issue. The spat was resolved by an agreement to progress negotiations on new international tax standards being drawn up by the OECD. But the jury is still out on whether these talks will succeed in making multinational digital firms pay their fair share towards providing public services.

The growth of the digital economy during the first years of the century saw a number of pioneering start-ups morph into global behemoths, reaping astronomical profits in the process. This development alerted governments around the world to the fact that they were missing out on potentially large amounts of tax revenue, according to Michael Devereux, director of the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation. “A feeling emerged among countries that Google and other firms were where the money was and that maybe they could get some tax income,” he says.

The rapidly changing face of the world economy also served to exacerbate existing problems with the century-old system of international tax rules, according to Sol Picciotto, emeritus professor at Lancaster University and chair of the advisory group of the International Centre for Tax and Development. “It became quickly apparent that, although digital companies were at the forefront of the debate, there were more fundamental problems with the system.”

In 2013, a report by the OECD backed this school of thought, placing the issue of digitalisation in the wider context of globalisation. It said that a shift away from country-specific operating models had created opportunities for multinational firms to greatly minimise their tax burden, meaning “many governments have to cope with less revenue and a higher cost to ensure compliance”. The problems were undermining the integrity of the tax system “as the public, the media and some taxpayers deem reported low corporate taxes to be unfair”, the OECD said.

Existing tax rules are based on the principle that businesses pay tax to the country in which they are physically located. The current regime was established some 100 years ago, well before digital businesses existed. Glyn Fullelove, president of the Chartered Institute of Taxation, notes that “back then, the mere act of selling something didn’t create value. All the value was in making it in the first place”.

Prior to digitalisation, companies manufactured in one country and exported to another. However, in most cases, tax authorities in countries where the goods were sold were able to tax a retailer or distributor with a presence in their territory. Devereux points out how broken this model is in a digital age. “Google’s Ireland office could sell an advert to a company in Switzerland for a service delivered in the UK. Because no money is changing hands in the UK, it is currently impossible to tax that.”

In addition, many digital businesses rely on their users to help create their value. Every time a teenager uploads a cute photograph of their pet dog, it creates a small amount of traffic from their friends. Cumulatively, this traffic helps social media companies sell ads and increase their profits. “These are not customers in the traditional sense,” says Fullelove. “They are a fundamental part of the business model and the tax system doesn’t deal with that.”

The second knotty problem – pre-dating the internet era, but exacerbated by it – relates to the problem of profit-shifting by multinational companies. Global firms are often able to avoid higher rates of tax by making clever use of subsidiary companies in low-tax jurisdictions. “A company in a higher tax economy often creates a product and sells to another part of the multinational in a lower-tax country,” says George Turner, director of the TaxWatch campaign group. “So the first company just covers its costs and doesn’t make enough profit to pay significant tax.”

In 2013, the OECD launched an initiative entitled the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project in an attempt to tackle these issues. In 2015, a 15-point action plan was announced by the OECD and G20 nations, outlining a route to the creation of a new tax regime.

"Google’s Ireland office could sell an advert to a company in Switzerland for a service delivered in the UK. Because no money is changing hands in the UK, it is currently impossible to tax that." - Michael Devereux, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation

Last year, negotiations resulted in the approval of consultation documents outlining two ‘pillars’, taking different approaches to the issue. The first pillar would create two new categories of profit for digital and consumer-facing businesses selling products created by other companies – ‘routine’ and ‘residual’. The debate about how these categories are defined has not been completely settled, but, in simple terms, residual profits relate to “intangible” advantages enjoyed by large companies, such as intellectual capital, distribution rights and computer systems. “The idea is that big multinationals get above-average profits from economies of scale,” Picciotto says.

The OECD proposals would see a proportion of residual profits made by a parent company – above a threshold – shared between jurisdictions in which it operates – for example, on activities targeting consumers in that country via online marketing. Calculating the proportions of these categories for individual companies will be complex, so experts predict that the OECD is likely to pick a fixed percentage, perhaps by sector. “In the end, it will be a political decision as to what the OECD says the number is,” Turner says.

The second pillar would build on previous work undertaken to reduce profit-shifting activities. The consolidated financial statements of a multinational firm could be used to work out a tax base for its global income. The pillar would create a minimum global tax rate for all companies. Tax payments would fall due on the proportion of profits that escaped tax in countries whose rates fell below this minimum.

In February, an OECD analysis said the combined effect of the two-pillar solution could raise up to 4% on top of existing corporate tax revenues – equivalent to around $100bn. According to the analysis, pillar-one reforms would bring “a small tax revenue gain for most jurisdictions”, with low- and middle-income countries expected to benefit more than advanced economies. Pillar two could raise “a significant amount of additional tax revenues” and lead to a significant reduction in profit shifting by multinationals, helping developing economies, which “tend to be more adversely affected by profit shifting than high-income economies”, the OECD said.

$100bn- Amount that could be raised on top of existing corporate tax revenues, as a combined effect of the OECD’s two-pillar solution

The losers would be the countries that the OECD politely terms as ‘investment hubs’ and others call ‘tax havens’. In 2018, academics labelled Ireland the world’s biggest tax haven. The paper said that, in 2015, Ireland’s effective corporate tax rate of 4% saw foreign multinationals shifting $106bn of corporate profits to the country. At the time, the Irish government disputed the findings, but, speaking in January, its finance minister Paschal Donohoe said his department is providing for a loss of €2bn by 2025 as a result of the OECD proposals.

However, the success of the proposals is far from guaranteed. “At the moment, the talks are on a knife edge,” says Devereux. “Some nations favour pillar two and others favour pillar one. It might be that this dynamic helps both get implemented – you might be a big pillar-one supporter and reach a deal with a pillar-two-supporting nation to support each other’s favoured outcome,” he says.

Fullelove is optimistic that a deal of some sort will be thrashed out, not least because of the risks involved in the alternative. “If we don’t get a deal, every country will decide it wants to introduce its own regime, which will involve retaliatory tariffs being imposed by countries whose companies are hit,” he says.

$106bn- OECD estimate of profits shifted to Ireland under the country’s effective corporate tax rate of 4%

However, even if a deal is reached, experts agree that the new regime is unlikely to provide a permanent and therefore stable solution to the taxation of multinational digital businesses. Reaching agreement between the 137 OECD countries involved in the discussions will not be straightforward, experts believe. As a result, hopes that a robust tax rate will be agreed are low. “It will be weak,” says Picciotto. “The best you can hope for is that the lowest common denominator will be adopted.”

This means the gulf between the amount being paid by digital multinationals and traditional businesses will be narrowed, rather than removed, according to Fullelove. “If we have Google and Facebook being taxed at a level of around 13%, say, and traditional manufacturers and retailers being taxed at 25%, it doesn’t sound like a recipe for long-term stability. Any agreement is just likely to be a step on a journey.”